Docker - runc, containerd, and the OCI

Note: “Docker: Its components and the OCI” is the second part of a mini-series that covers fundamental concepts and core components of Docker and takes a brief look at further technologies in the container space.

In its early days, Docker was a monolithic application responsible for creating and running containers, pulling images from registries, managing data, and so on. Pretty much everything that Docker does today was part of that monolith. Since Docker version 1.11.0, the monolith has been decoupled into a set of independent components that follow well-defined standards. This decoupling and standardization process drove contributions by the open-source community, and new projects started to emerge in the container ecosystem.

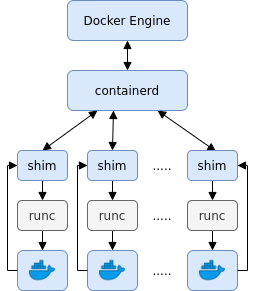

The following figure shows a high-level view of the components that Docker consists of nowadays:

The Docker Engine is a high-level component and is at the top of the architecture. When you use the Docker CLI or API, you communicate directly with the engine following a client/server model. The Docker Engine itself does neither create nor run containers directly, but rather initiates their creation. It provides management capabilities like building new images, setting up the storage, collecting logs, running health checks, executing, and responding to, user and API requests, and so on. On the layer below, containerd provides supervision to containers and manages their lifecycle. It is containerd that pulls the container image from a registry and creates a bundle based on the image and the parameters provided by the Docker Engine. The bundle is then forwarded to runc, the container runtime for Docker, via the shim process. runc sets up the required Linux primitives (cgroups, namespaces, etc.), starts the container, hands over the container to the shim process, and exits. The shim can be seen as a parent process for the container and is a layer between containerd and runc that enables daemonless containers. While containerd and runc do the heavy lifting when a new container gets started, the shim process decouples the container from the runtime and avoids long-running runtime processes. Further, it keeps the STDIO and additional file descriptors open so that the container keeps running independently of runc, containerd, and the Docker Engine. Hence, containerd and the Docker Engine can be upgraded or restarted without affecting running containers.

In 2015, Docker began to open source some of its components, starting with runc. Together with other industry leaders, they formed the Open Container Initiative (OCI) with the objective to create open industry standards around container formats and runtimes to support the container ecosystem. Hence, the OCI standards facilitate interoperability between container-related technologies. As of now, the OCI contains a runtime specification and an image specification. runc as the initial project fully complies with OCI standards. Hence, if you are using Docker, you can replace runc with any container runtime that follows OCI standards. Additionally, you could build your own management solution for containers and use runc as a container runtime, taking advantage of the stability and flexibility the OCI provides for projects and applications relying on runc.

Besides, Docker contributed containerd to the open-source community as well. Likewise, it follows OCI standards and is part of the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF). containerd has a highly modularized architecture and an active community that continuously maintains and improves the project.

Both runc and containerd are widely used in the container ecosystem, and many projects evolved around them. While runc is often fully adopted as a container runtime, other open-source projects utilize the modularity of containerd and re-use only parts of it. Hence, the last part of this article focuses on containerd and its architecture.

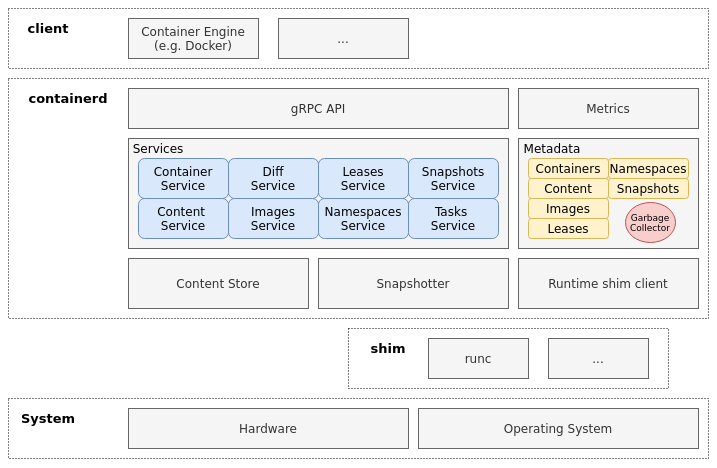

The following figure shows a high-level view of containerd’s architecture and how it fits into the container ecosystem. Some details are left out for clarity, but for a complete picture, I recommend to look at the official website containerd.io.

The architecture is built around the creation and execution of so-called bundles. A bundle is basically a directory on the file system and represents an on-disk container. It consists of metadata, configurations, and the root filesystem for the container. Once containerd has created the bundle, it can be packed up, distributed, or passed along to the container runtime to run the container. As containerd follows OCI specifications, any OCI compliant runtime can be the receiver of such a bundle.

containerd consists of modular, loosely coupled services that can be accessed via the gRPC API. The task service, for example, is active when running containers. It creates the shim process and initiates the communication with the container runtime (via the shim) to start the container. Also, containerd utilizes namespaces and provides a distinct namespace service. However, these are not related to container namespaces (which get created by the container runtime) and enable multi-tenancy for containerd, i.e., multiple clients can leverage the same containerd instance without interfering with each other. Besides, additional services are available to interact with container images, create bundles, create or modify configurations, manage metadata, and access monitoring and reporting data of containers.

Before containerd can create a bundle and run a container, the container image must be loaded into the content store. For most use-cases, this happens via a download from a registry, but it is also possible to load content directly into the content store. Its representation on the file system is very similar to how registries store their images. For each layer, there exists a file with the hash value as the file name. Additionally, the content store creates a file for the index, the manifest, and the config and assigns labels to each layer. containerd uses this metadata to organize its content and when it creates the bundle. Data in the content store is immutable and stored on the file system. You can check its default directory at “/var/lib/containerd/io.containerd.content.*”.

Another essential component is the snapshotter. Content in the content store is often in a format that is unusable for containerd, e.g., many container layers are in a tar-gzip format that cannot simply be mounted. containerd creates snapshots of the content to ensure the immutability of the content store. For each layer in the content store, the snapshotter creates a new snapshot-layer by applying the blob of the current layer on top of the snapshot from the parent layer. Hence, each layer in the content store has a corresponding immutable snapshot layer. After a snapshot has been created, containerd only uses these snapshot layers in further steps.

Due to its modularity, developers can extend containerd with fairly easy or build their own version of it. For example, someone could develop their own snapshotter to handle specific file formats. For that reason, containerd provides a highly extendable client library, supports built-in and proxy snapshot plugins, and allows runtime extensions based on the shim API. For example, to integrate a new runtime with containerd, it suffices to develop a runtime plugin that inherits the shim API.

If these options are still not sufficient, a viable solution would be to check out the source code of containerd, replace only the components that do not fit the use-case, and simply build a new version of it. Hence, containerd provides a lot of flexibility to either extend or adapt its components to support a variety of use-cases.

To sum it up, containerd alone would be enough to write multiple blog articles about. For anyone interested in reading more about it, the documentation in the GitHub repository is a good starting point, in my opinion. For example, the design descriptions and the docs folder in the repository. Additionally, talks on YouTube, e.g., from DockerCon, provide further insights into containerd.